Before beginning the second instalment in this series of film reviews, let’s revisit the criteria.

Is the cast “diverse” only in a way that comports with historical facts, contemporary realities, and/or source material?

Is the film made with little to no CGI?

Does the film edify the audience?

Could the film be made today exactly as it was in its time? (Here, a negative answer is required.)

Remember, too, that the films in this series won’t necessarily be great ones. While there may be exceptions, don’t expect Oscar-winning movies or arthouse cinema. Indeed, some of the films in this series might struggle to qualify as good films, but they will have met the above criteria for being an edifying film from a time when movie-makers weren’t so terribly obsessed with subverting audiences, history, and source material..and nation-states for that matter. One of this type of movie is the next entry in our collection.

Boomers in Space!

Let us return to the year 2000, the dawn of the new millennium. Trepidation over Y2K has subsided and September 11, 2001 is yet to arrive. There is only the thrill of discoveries waiting to be made, horizons yearning to be reached. Space Cowboys was a summer “popcorn flick” that captured some of that expectant enthusiasm. It’s a film that returns the audience to America’s glory days, while showing that America is able to do the impossible even in the coming age.

Space Cowboys, directed by and starring Clint Eastwood, tells the story of four old timers, veterans of the United States Air Force, and their unlikely mission into outer space.

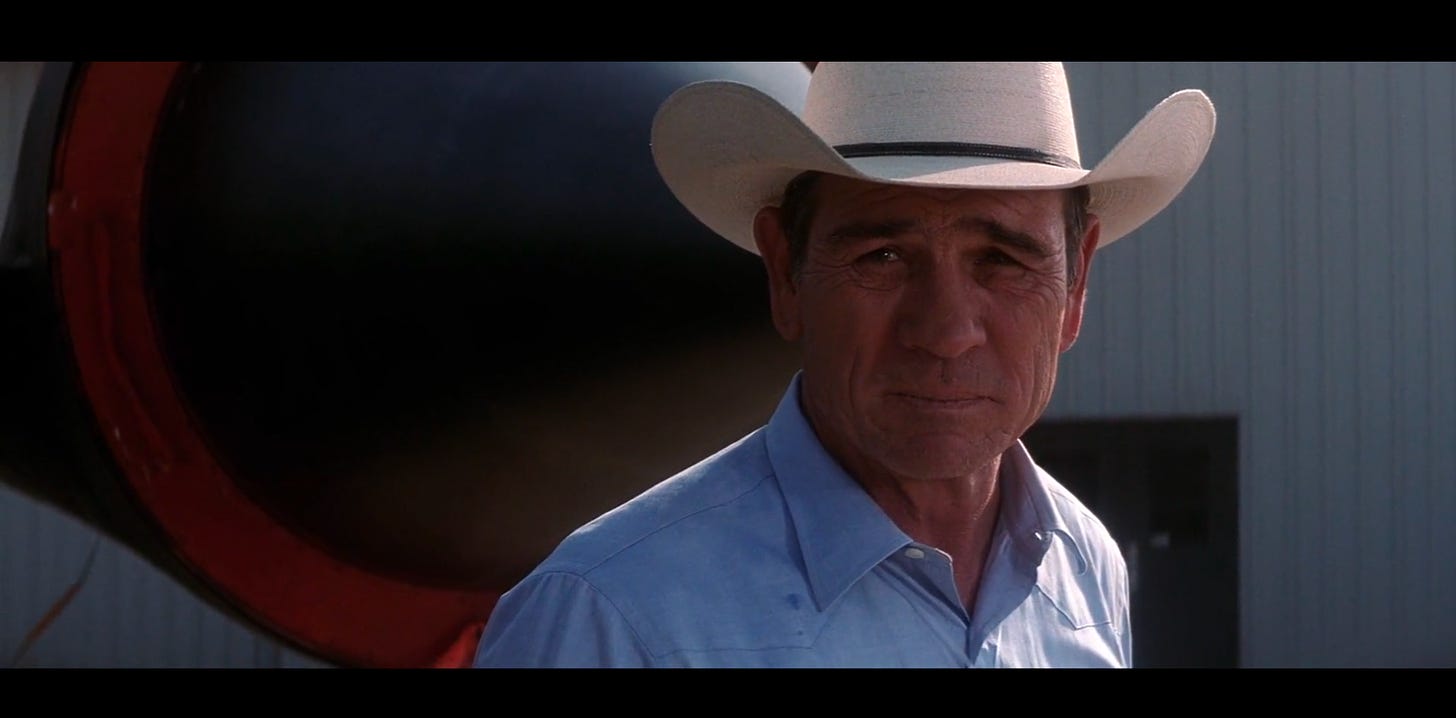

It begins with a flashback to 1958. The aptly named William “Hawk” Hawkins and Frank Corvin are test-flying a Bell X-2 aircraft. Hawkins, later portrayed by Tommy Lee Jones, wants to push the machine to its very limits. While testing the speed and altitude capacities of the Bell X-2 is what they are supposed to do, Corvin, later played by Eastwood, isn’t too keen on destroying the plane or losing his life in the process.

But Hawk doesn’t listen to Corvin’s warnings. Instead, he looks longingly at the moon hanging in the daytime sky and tells his co-pilot, “That’s where we’re going. I don’t know how and I don’t know when, but…” he trails off and then starts singing Fly Me to the Moon.

Inevitably, Hawk pushes the plane too high and too fast. The engine stalls and the aircraft becomes unresponsive. Hawk and Corvin are forced to eject, and all the while the adrenaline-loving Hawkins keeps whoopin’ and hollerin’ in his Texas accent. Both pilots parachute to earth safely, but straight-laced Corvin is incensed and punches Hawk in a foreshadowing of many altercations to come.

This is followed by the obligatory scene wherein the pilots are reprimanded by their superior, Major Bob Gerson. Gerson, who will later be portrayed by the iconic character actor James Cromwell, then leads Hawk and Corvin to a hangar where several reporters are awaiting an announcement from the Major. Joining the pilots are their two flight engineers, Jerry O’Neill and Tank Sullivan. These four men comprise Team Daedalus.

As the old-timey camera bulbs burst, Gerson declares that the US Air Force will no longer be involved in “outer atmosphere testing and exploration” and that Project Daedalus is complete, with the rest of the work to be passed on to a civilian organisation called the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

While still stunned by this news, the young men of Team Daedalus are further insulted when Gerson brings on stage the person who will take their place as the first American to go into outer space: a chimpanzee named Mary Ann. It is a wound that the boys won’t forget, especially Frank Corvin.

The story now jumps to present day, the year 2000. We are taken to NASA headquarters where a situation is developing. A Russian communications satellite called Ikon has fallen into orbital degradation, suffering a total systems failure. In a little over a month, the satellite will enter Earth’s atmosphere and then crash. The Cold War having thawed many years ago, relations between America and Russia are much improved. A Russian general is on hand to assist the Americans in their assistance of the Russians in deciding what to do about the satellite. He says that losing the satellite is “not an option.” For reasons he doesn’t really explain, should Russia find itself without the services of Ikon, even temporarily while a replacement satellite is sent up, the country would plunge into civil war.

None of this makes much sense to Sara, a NASA engineer played by Marcia Gay Harden. Her boss overrides her suspicions and objections, however. And just who is Sara’s boss? None other than Bob Gerson, now a head honcho at NASA.

Sara catches up with the technicians trying to figure out how to fix the Russian satellite. While IBM computer screens flash green letters and numbers and large scrolls of the satellite’s blueprint smother desks, they admit to her that it’s a bust. The technology is so outdated, no one understands it. The “guidance system” is described as “Byzantine”, “a mess”, and a “dinosaur” that is “pre-microprocessor”. None of the fresh-faced engineers know what to do with this hunk of old Russian junk.

But Sara finds out that the guidance system comes from something called Skylab. Skylab is American. There is some momentary incredulous surprise that an American-designed guidance system is on a Russian satellite, and then Sara determines to look up the designer. Gerson tells her to save her time. He already knows who the designer is. His nemesis, the man he butted heads with and insulted back in '58: Francis Corvin.

With the plot starting to take off, we now follow Sara and a hot-shot astronaut named Ethan as they show up on Frank Corvin’s doorstep with a proposal: help us fix a satellite with your guidance system installed on it before it enters the Earth’s atmosphere and is destroyed.

Clint Eastwood plays Frank Corvin as the kind of man we come to expect from him. He’s as smooth as sandpaper, both in manners and physical appearance. It seems like Eastwood’s been playing the same character for about four decades or so, but would you really want him to do anything else? This is who he is. This is what he does best. Frank scowls and grunts and occasionally lets loose a few grumpy barbs while Sara tries to convince him to help NASA. It’s not an easy task, particularly after Frank learns that his system is on a Russian communications satellite.

“You designed this system,” Sara pleads. “If anyone can solve this problem, it’s you.”

Things get even worse when Sara and Ethan are forced to admit that they work for Bob Gerson.

“I think it’s time for you two to head on out of here,” comes Frank’s response, adding that he hopes the satellite lands on Gerson’s house.

As Ethan heads for the door, he returns fire. “You’re not a team player. That’s why you washed out at NASA.”

“Get out,” snarls Corvin.

But of course, the story doesn’t there. We see Corvin in deep contemplation for a few moments and then we’re back at NASA HQ and Corvin is leaning into Sara’s office. “I think I have a solution for your problem.”

Now comes the tense reunion between Corvin and the man who snatched his dream of going to outer space and gave it to a monkey. There is sarcasm and restrained insults aplenty, and then Frank finally reveals his solution. “Send my team up. We’ll fix your broken satellite.”

Gerson can barely believe what he’s heard and Sara acts like she had no idea, which is true enough. Then Corvin and Gerson have a verbal sparring session. Corvin essentially blackmails Gerson by reminding him that he’s the only one who understands the guidance system and Gerson reminds Corvin that he’s an old man well past his prime, a senior citizen in no condition to fly to stars.

They seem to be at an impasse but just as Corvin is about to leave the premises, Gerson stops him. Corvin and his geriatric buddies, if they’re even alive, can go up to the satellite only if each and every one of them passes the physical fitness tests, and only if Corvin agrees to train and work alongside Gerson’s own hand-selected crew.

So Frank heads off to find the other members of Team Daedalus. Tank Sullivan, now played by James Garner, has become a Baptist minister. Frank teases him by saying he brings news of a resurrection. It doesn’t take much for Sullivan to shake hands with his old pal and accept the mission.

Next up, Frank locates Jerry O’Neill, now played by Donald Sutherland. Jerry sports long white hair tied in a ponytail and is spending his winter years building roller-coasters. He is also a lascivious rake who, when we meet him, enjoys the company of a fit young babe.

Frank saves the most challenging ex-crewmate for last. “Hawk” is in Utah. Still the adrenaline junkie, he is living out his retirement by giving thrill rides to paying passengers in his fire-engine-red Boeing-Stearman 75.

After taking an overly eager yuppie to the edge of his life, Hawk lands back on the airstrip and finds Frank waiting for him. There’s a bit of “will he, won’t he” tension as Corvin tries to persuade his old pilot to rejoin Daedalus, but in the end, Hawk gleefully agrees.

Here is where Space Cowboys really takes a comedic turn which will last for most of the film’s second act, and it’s the best part of the story. It’s also why I chose Space Cowboys to be a part of this series.

The twenty-four years after the release of Space Cowboys saw America, and latterly several European countries, poisoned by anti-white and anti-male venom. It was during those years that it became normal, even encouraged, to mock and criticise anything “pale, male, and stale”, although I was surprised to learn that the phrase “pale, male, and stale” actually originated in 1992, coined by—would you believe it—NASA administrator David Goldin. Rather fitting, then, that Space Cowboys should tell the story of four pale, stale males who have to save NASA’s (increasingly non-white) skin.

We watch as the old friends are put through their paces, trying their best not appear too tired or too weak. There are several poignant moments, wrapped in a warm blanket of good-natured humour, that show us the pains and melancholia which come with getting old. But even though their bones are aching and their dentures might be falling out, the old chaps keep a brave face and an indomitable spirit. Jerry even flirts with the red-headed lady doctor assigned to give the men their physical exams. The past is a different country. Nowadays, Jerry either wouldn’t dream of flirting with a female colleague, or he would flirt out of naïveté and end up getting the “Me Too” treatment.

Running ten miles proves to be a tough challenge for Team Daedalus, but they manage to complete it. Other tests, like being strapped into a rig designed to replicate the G-force of a shuttle launch, Hawk and Corvin pass with aplomb. As for the technical tests? Don’t even mention it! The old timers are able to solve problems and execute difficult manoeuvres, and do so without the aid of computers—something that astonishes the digital-tech-dependent young trainees.

The days to launch keep counting down. Some muckraking paparazzi snap photographs of the senior citizens dressed in their NASA training uniforms, and the next day their faces are all over the front pages. For a brief moment, this appears to be a problem, but then Gerson and Co. decide to embrace the attention. Team Daedalus become minor celebrities. They are invited on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno. The American people fall in love with these charming old rascals. It’s all so wholesome.

Everything seems to be going smoothly. That is, until the results of their physical inspections arrive. Each member passed his test, except one: Hawkins. It wasn’t that Hawkins couldn’t run ten miles or see at 20/20 vision. No, his is a much more serious failing. His tests revealed that he has inoperable pancreatic cancer. This would seem to represent an insurmountable obstacle, but the film again resolves the problem with a quick scene in which Gerson and Corvin have another argument which ends with Gerson’s sighs of resignation. It’s too late to cut Hawkins from the team. He’s the most popular member after his performance on TV, and the cancer hasn’t stopped him from doing what an astronaut needs to be able to do. Hawk stays.

The second act comes to its close and now we are all set for the launch into outer space. Unfortunately, this is where the movie begins to go wobbly. What was up until now a tender and comedic portrayal of friendship, rivalry, aging, and generational differences, suddenly becomes a suspenseful drama, albeit a rather ridiculous one.

After Hawk flies the shuttle Daedalus into space and the crew, consisting of the four space cowboys and two young NASA astronauts, one of whom is Ethan, has settled in, they begin to approach the Russian satellite. Upon finding it, they discover that it’s hardly a communications satellite at all. It’s massive bulk of metal and panels, imposing and ominous. As they get closer, the satellite responds to the NASA spacecraft’s radar by initiating some sort of self-defence mechanism. The crew, and mission control down in Houston, are entirely baffled. And afraid.

They guide the spaceship next to the satellite without radar, while Baptist reverend Tank Sullivan inexplicably says a “Hail Mary”. Hawk and Frank then suit up and prepare to step into the void so they can climb onto Ikon and Corvin can get rid of whatever MacGuffin is troubling it. But instead of encountering an old satellite with his Cold War-era guidance system, Corvin finds himself inside the metallic guts of a satellite equipped with six nuclear missiles.

The filmmakers decided to turn Ikon into a character in and of itself. There’s no sound in space, but we hear the satellite groan and grumble like a metallic monster. We are made to feel like Ikon is a sleeping beast, an evil dragon that could wake up at any moment and roast the intruders in his domain.

Down in Houston, the Russian general we met before explains that the satellite was fitted with those missiles during the Cold War, and they are pointed at the six most important cities in America. This is why Ikon cannot be allowed to fall to Earth, and worse, having lost its uplink connection with the ground, it is programmed to launch the missiles. As I said, the plot gets wobbly here.

So now our astronauts are in a race against time and a battle against technology. As they convene amongst themselves and Houston, Ethan takes it upon himself to singlehandedly complete the mission. He leaves the shuttle and goes back to the satellite. Frank, his superior, repeatedly orders him to return to the ship but Ethan ignores each command. “I’m doing your job, Frank,” he says arrogantly.

The tension between old and young that was building during the physical training now reaches its climax. The hubristic Ethan disobeys his elders. Crusty old Corvin, who was supposed to teach Ethan everything he knows, kept his cards close to his chest and never told Ethan “the sequencing” necessary to put the satellite back into “geosync orbit”. If none of those terms make much sense to you, it’s because they’re not supposed to. What I found more compelling was the metaphor, perhaps unintentionally made, for the generational divide between Boomers and their descendants. Here we see the consequences of an old man refusing to pass on his skills and knowledge out of his own selfish desires, and the consequences of a young man who has no respect for his elders.

No surprise, Ethan’s actions throw the whole mission into chaos. He pushes some wrong buttons and plugs in something where it shouldn’t go. Literal sparks fly and Ikon begins to shed heavy metal panels as its six nuclear missiles engage. The debris falling off the satellite strikes Ethan and also lands on the space shuttle, knocking out its computer system. As Ikon’s wreckage continues to collide with space shuttle Daedalus, the other young astronaut, a token black character named Roger, is hit in the head and suffers a concussion.

So, now it’s up to the four space cowboys to stop Ikon from firing nuclear missiles at America, get the satellite away from Earth’s orbit, then repair their shuttle and fly it back home.

Frank and Hawk come up with a plan that is full of technical mumbo jumbo that makes just enough sense for the audience to pretend like they understand what’s going on. Meanwhile, we’re not sure what’s happened to Ethan. He looks pretty dead, floating out there in space, tethered just barely to the Daedalus.

There are some pretty impressive shots of the astronauts in outer space. Clint Eastwood was not meant to be the director of Space Cowboys when production began, but when difficulties arose regarding how to shoot the scenes in space, Eastwood assumed responsibility. It’s a testament to his skill as a filmmaker, and also a poetic reflection of the character he plays in the film, that he was able to pull off these parts of the shoot that no one else could.

Despite Eastwood’s vision and guidance, there are still numerous potholes in the final act. Hawk and Corvin again suit up and go out onto the satellite. They manage to make it static just before it launches the missiles, but now they have a problem. They only have one Payload Assist Module rocket, and it’s not enough to push the heavy Russian satellite into orbit far away from planet Earth. There is another problem too: Ikon’s panels have taken so much damage, they won’t generate enough power either.

Space Cowboys is almost 25 years old, so it can’t really be considered a spoiler if I tell you how the movie ends, but if you don’t want to know, skip these next paragraphs.

Hawk, recently widowed and diagnosed with deadly cancer of the pancreas, decides to sacrifice himself by strapping onto the satellite and using the nuclear missiles’ engines to propel it into deep space. Then, his idea goes, he will guide it towards the gravitational pull of the moon (a quarter of a million miles away) where it will self-destruct. The sheer distance to the moon makes this seem more than a bit implausible, and the fact that the missiles’ engines are remotely ignited by Corvin from the cockpit of the Daedalus would seem to make Hawk’s self-sacrifice unnecessary.

But there’s no time to ask questions. Still cracking jokes and smiling, Hawk is literally launched to the moon, rather unceremoniously I might add. The film would have been better served by slowing down and letting us appreciate the gravity (pun intended) of the situation and of Hawk’s sacrifice. I suppose the no-nonsense manner in which the crew agree to Hawk’s plan and then proceed to execute it is meant to be in character for the tough old timers, but let’s not forget that one of them is a priest. It would have been easy for Sullivan to say a prayer for Hawk, and for Hawk to say his goodbyes to his old friends. Instead, we get a smirking Hawk saying his last words, “Let’s shoot this baby to the moon!” while the rest of the team wonders if this will even work.

Now it’s down to Corvin, Sullivan, and O’Neill to land the Daedalus back on Earth in one piece. They have no computer systems and their pilot has just been strapped to six nuclear missiles and fired towards the moon. Corvin will have to take control of the shuttle and land it “dead stick”. More wobbly bits occur. As the Daedalus enters Earth’s atmosphere flying at about 17,000 miles per hour, Ethan and Roger are dumped out of the hatch even more unceremoniously than Hawk was launched to the moon. We still don’t even know Ethan’s condition. Is he dead? Just knocked unconscious? As for Roger, we do know that he’s knocked out. Who exactly is going to open these boys’ parachutes? Or have they recovered now? But how will they survive being thrown out of a space shuttle surrounded by fire entering Earth’s atmosphere at the speed of sound? Never mind!

The remaining members of Team Daedalus decide to stay together and literally go down with the ship. Frank manages to land it safely, using a technique he learned from his friend, William Hawkins. Mission control erupts in applause in a scene we’ve all become familiar with.

As the story ends, we are back with Frank and his wife at their home. They are looking up at the night sky and a big bright moon. “Do you think he made it?” Asks Frank’s wife. “Yeah, I think he did.” He answers.

The last shot before the credits roll takes us to the surface of the moon. The debris of Ikon is scattered on the dusty grey ground. The body of an astronaut is lying propped up against a mound, Earth reflecting back at us on his closed visor.

Sinatra croons Fly Me to the Moon once more and we fade to black. So concludes Space Cowboys.

When it was released in 2000, it received generally favourable reviews. Much praise was said of the actors, rightfully so. They are all consummate professionals. Tommy Lee Jones is perfect in the role of the happy-go-lucky Hawk and Sutherland is deftly able to shift from a jovial—if a little too leery—Lothario, to a serious flight engineer and astronaut. James Gardner seems rather underused, but doesn’t get a step wrong with what he was given to work with.

The first two-thirds of the film also received deserved positive reviews, but that final third is where the potential 5 star rating falls down into the 2 or 3 star range.

I enjoyed the first two acts especially for what they have to say about old white men. I couldn’t help but think of the deep sea submersible Titan. In 2023, Stockton Rush, the CEO of tourism company OceanGate, met his death and caused the death of four others when his submersible imploded due to shoddy construction. Prior to his demise, Rush had stated that he didn’t hire “Fifty-year-old white guys” to captain his vessels because they weren’t “inspirational” enough.

For all the flak that old white guys take, if you want something done well, they really are your best option. Space Cowboys takes us back to a time when this fact was starting to be undermined and unapologetically tells us “not so fast.” Even the name of the crew, Team Daedalus, is a nod to this fact; the eponymous Greek deity being a wise old craftsman.

Returning to our time, the year 2024, and another “white guy” is once again making space exploration and rockets look cool. Whether you want to go to the moon, go to Mars, or just fix an old Russian satellite, you need The White Man for the job. The other races of the world, the races who now fill up the United States, and many white people themselves, should remember that. Instead we get constant anti-white and anti-male grievance grifting. A film like Space Cowboys would certainly never get made today, not unless at least half of Team Daedalus were race-swapped or gender-swapped.

It won’t be the best film you’ll ever see. You might even like it a lot less than you did at the start by the time the end credits appear, but Space Cowboys remains a wholesome bit of two-hour-long entertainment that does not subvert nor corrupt, but instead treats its characters with the respect they deserve.